IF UBER DID SUPPLY CHAINS…

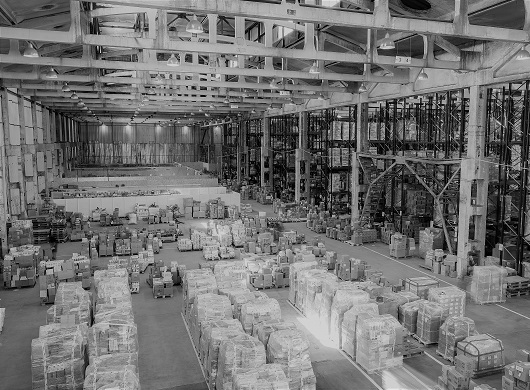

In supply chains, where product is a ticking time bomb of shelf life, speed is crucial. We see the common model is to hold stock in three locations: the store, the retailers’ distribution centre and the manufacturer’s own warehouse.

This doesn’t feel efficient when you add in the fact that each of the stock points needs a person to manage it, someone to put it away and to take it back out. The incremental time lost at each point is time lost on the shelf, which ultimately is a major driver of waste, multiplied by a forecast and decision error at each point, otherwise known as the bullwhip effect.

If we look to the Uber and Airbnb models, an important question comes to mind: can these concepts be applied to supply chains and, more importantly, would they add any value?

Firstly let’s deconstruct what these disruptor models actually are;

In the basic form they cut out part of their supply chain, use assets they do not physically own (which would otherwise be idle) and do all of this through the use of technology and faster sharing of information.

Switch back to the retail world and imagine a supply chain where the stock flows off the production line, straight onto a truck which heads to the retailer’s distribution centre as the single stock point. The stock level is then managed by the manufacturer, but the retailer provides warehousing and the distribution. Once it leaves for the store, the retailer takes ownership and information on sales by store is provided directly to the manufacturer in real time, as does the stock position in each DC while being connected to the planning and ERP systems of the manufacturer.

This is going to push stock at the retailers’ DCs up by a huge amount, isn’t it?

Well, we think not. Manufacturers know their products better than anyone and can use discrete, not global, algorithms to predict demand when source data is available for their own product: a better prediction equals a lower stock requirement. Additionally, we already know it’s common for both retailer and supplier to have up to 25 per cent of product life sitting in stock, meaning each stock point is there for the variability of the next, and may not be required if the step is removed.

Yes, OK, but surely some loses?

The retailer has higher capital costs to expand DC networks, but this frees up huge amounts in working capital as they no longer own the stock. In addition, it creates a new income stream for storage space, removes a large part of unnecessary back-office overheads and involves an increase in customer service.

The manufacturer may take on a slight increase in working capital, remove somewhere between 10 and 40 per cent of its footprint, most of its warehousing costs and take ownership for end customer service with no option to moan at the retailer’s terrible forecasts going forward.

If it’s that simple, why is nobody doing it?

The retailers are retailers and the manufacturers are manufacturers.

Until someone is ready to challenge this model, we will all be stuck eating our fresh food several days after it was produced and paying a premium for the privilege.

Paul Eastwood, Director; Pollen Consulting Group

First published in Retail World:

https://www.retailworldmagazine.com.au/emag/2019/RW-APR-2019/index-h5.html?page=1#page=56